Rachel Lee, Walton High School (Marietta, GA)

Since Fleming’s discovery of the first antibiotic penicillin in 1929, antibiotics have come a long way to become one of the most common classes of drugs worldwide. Antibiotics are used for various purposes that range from treating the most common bacterial infections to preventing potential infections in wounds from surgical operations. Despite their common usage, they are not a magical cure-all drug that can be administered for every disease.

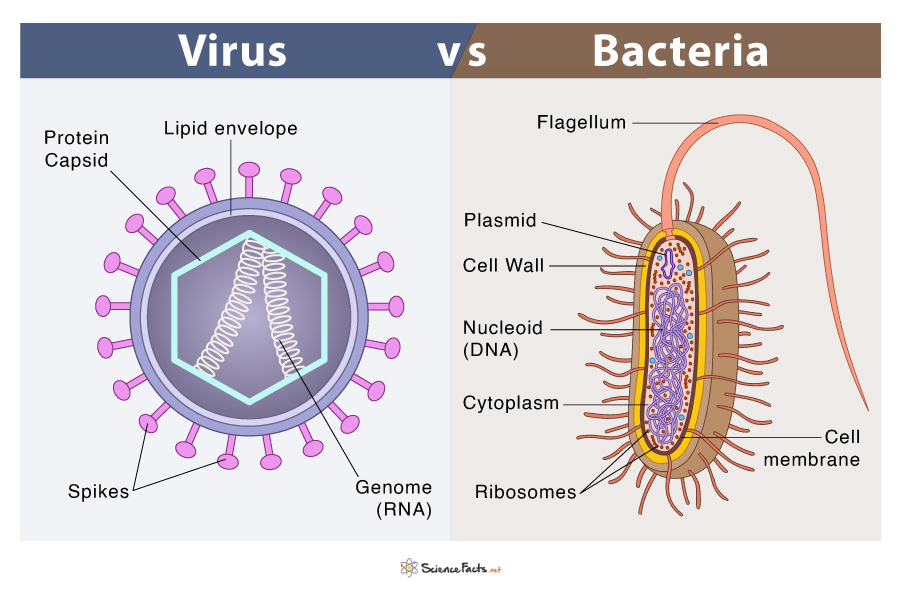

The key word in the function of antibiotics is ‘bacterial’. That is, antibiotics are only capable of treating bacterial infections, not viral ones. The reason behind this lies in their mechanism. Antibiotics disrupt essential processes and structures in bacteria by inhibiting targeted biomolecules.¹ These include preventing cell wall formation, breaking up cell membranes, and disrupting ribosome functions.

While viruses and bacteria are often grouped together as pathogens that spread in similar ways, they have more differences than similarities. Most importantly, unlike bacteria that are prokaryotic (without a nucleus) cells, viruses are really only composed of genetic material inside a coat of protein. They do not have any specific cellular structures or compartmentalization, and are not considered cells. Therefore, since viruses do not have the cellular structures and functions that antibiotics target in bacteria to begin with, antibiotics simply have no effect at all in treating viral diseases.

Correct usage of antibiotics is especially important due to the issue of antibiotic resistance. Bacteria reproduce very quickly – it can double its population every 4 to 20 minutes.²

When they replicate, bacteria with mutations that make them resistant to an antibiotic are naturally selected for (since they are the ones in the population that would be able to withstand the effects of an antibiotic and grow). As the antibiotic-resistant bacteria reproduce, the mutation and the resulting resistant characteristic can be imparted to new members of the reproduced population. When antibiotics are frequently used to treat trivial conditions, it is more likely and easier for bacteria to develop resistance. Even when antibiotics are misused for conditions they are ineffective against, such as viral infections, it can promote antibiotic-resistant properties in harmless bacteria in our body, which can be shared with potentially harmful ones in the future through DNA transfer (bacteria can share genetic information with other bacteria through horizontal gene transfer, including resistant DNA).³ This makes it harder to treat future serious conditions using that antibiotic.

But are there not plenty of different antibiotics out there? Surely we could spare bacteria developing resistance to just a few of them, right? Not exactly. First, it goes without saying that having multiple treatment options is always beneficial. It allows professionals to administer the most effective antibiotic as quickly as possible and prevent harmful or even lethal consequences.⁴ However, the real problem lies in the fact that we are running out of effective antibiotics. Even though efforts are continually being made to develop new ones, the efforts simply cannot match the speed to which bacteria can develop resistance. For example, in a 2019 WHO report, they identified 51 new antibiotics in clinical development, but only found 8 to be of innovative value to current antibiotic treatment methods.⁵ Not only that, there is also the threat of “superbugs”: bacteria that have resistance against numerous types of antibiotics, which lead to increased rates of death and disability worldwide.⁶ Likewise, the world’s finite options of antibiotics makes antibiotic resistance “an urgent global public health threat, killing at least 1.27 million people worldwide”, according to the CDC.⁷

While most antibiotics must be prescribed by a healthcare professional in the United States, research has found that still 28% of antibiotic prescriptions from doctor’s offices and emergency departments are unnecessary.⁸ Therefore, with the line of antibiotic defense we have getting weaker and weaker, it is important for not only healthcare professionals but also the general public to be aware of proper antibiotic usage. Perhaps the bleak future of bacterial disease that we face may improve if we try and avoid the misuse and overuse of antibiotics.

Here are the antibiotic do’s and don’ts advised from the CDC⁹:

Antibiotic Do’s:

- Use antibiotics when you have serious conditions of certain types of BACTERIAL INFECTIONS, such as strep throat, whooping cough, urinary tract infection (UTI), etc. (“Some infections caused by bacteria can still get better without antibiotics. You DO NOT need antibiotics for some common bacterial infections, including many sinus infections and ear infections.”)

- Use antibiotics if you get them prescribed, and use exactly as prescribed.

Antibiotic Don’ts:

- Do not use antibiotics for conditions caused by VIRUSES, such as colds, runny nose, most sore throats (except strep), the flu, most cases of chest colds (bronchitis), etc.

- Do not share your prescribed antibiotics with others or take someone else’s antibiotic prescription.

- Do not save excess prescribed antibiotics for later or take someone else’s antibiotic prescription. Taking the wrong medicine can delay correct treatment and instead cause side effects.

From CDC’s Antibiotic Prescribing and Use – Healthy Habits: Antibiotic Do’s and Don’ts (visit the link for more details: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/about/index.html)

References:

- Kohanski, M. A., Dwyer, D. J., & Collins, J. J. (2010, May 4). How antibiotics kill bacteria: From targets to networks. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro2333

- Pacific Northwest National Laboratory . (2021). PNNL: Just how fast can bacteria grow? it depends. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. https://www.pnnl.gov/science/highlights/highlight.asp?id=879

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2024, April 9). Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/antibiotics/art-20045720#:~:text=If%20you%20take%20an%20antibiotic,be%20shared%20with%20other%20bacteria.

- Cleveland Clinic medical. (2024, May 1). What is antibiotic resistance?. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/21655-antibiotic-resistance

- World Health Organization. (2017, September 20). The world is running out of antibiotics, WHO report confirms. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/20-09-2017-the-world-is-running-out-of-antibiotics-who-report-confirms

- NHS. (2022, November 11). Antibiotic Resistance. NHS choices. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/antibiotics/antibiotic-antimicrobial-resistance/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 22). About antimicrobial resistance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/about/index.html#:~:text=Antimicrobial%20resistance%20is%20an%20urgent,5%20million%20deaths%20in%202019.

- Hersh, A. L., King, L. M., Shapiro, D. J., Hicks, L. A., & Fleming-Dutra, K. E. (2021, January 23). Unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in US ambulatory care settings, 2010-2015. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32484505/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 22). Healthy habits: Antibiotic do’s and don’ts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/about/index.html